This paper discusses in detail the treatment and observed outcomes of two children with spastic cerebral palsy who received Myofascial Structural Integration, a manual therapy that directly targets the myofascial system. It emphasizes the many qualitative and quantitative improvements observed, from the therapist, parent, and patient perspectives. It also briefly reviews three previously published studies on the benefits of Myofascial Structural Integration for Young Children with Spastic Cerebral Palsy, including suggestions for additional research with this population. Children with spastic cerebral palsy often experience difficulty with ambulation among other impairments. Structural changes in muscles and fascia may play a role in abnormal movement. Previous formal study outcomes have focused on quantitative data about mobility and found modest improvements. Through the two case studies, this paper will address other quantitative as well as qualitative improvements such as: increased height and weight, improvements in the quality of movement, balance, and coordination, increased confidence, and more maturity. It also discusses the evidence validating Myofascial Structural Integration as a modality to effect change in structure, posture, and myofascial tissue, and encourages additional research to support the many benefits observed in the studies and in clinical practice

The overall aim of this paper is to advocate for Myofascial Structural Integration (MSI) as a treatment forchildren withcerebral palsy. I will introduce two children in detailed case studies, each of whom had spastic cerebral palsy (CP). Although the severity of their CP diagnoses and corresponding functional manifestations were different, both benefitted in many similar ways from MSI. This paper will explore those qualitative benefits and offer suggestions for further research.

Myofascial Structural Integration (also known as Rolfing® and Structural Integration) is a specific manipulative-and movement-based complementary medicine practice developed by Dr. Ida P. Rolf, PhD (1896-1979) beginning in the 1930’s..Throughdeep tissue manual manipulation, the trained practitioner brings the myofascial system towards greater anatomical alignment, which increases stability and improves balance, mobility, and motor patterns.

Cerebral palsy is a disorder of movement, tone and posture. The impairments of CP always involve motor function, while other cognitive and sensory impairments are often present. The most prevalent type is spastic cerebral palsy, resulting in increased velocity-dependent sensitivity to stretch, causing stiffness, tightness, and interference with movement. Over time, spasticity can lead to joint contracture and deformity.Increasing evidence suggests that the spasticity of cerebral palsy is not due solely to the etiologic non-progressive brain injury, but that skeletal muscle and its extracellular matrix are also altered. Given that motor stiffness and increased collagen content in cerebral palsy may contribute to stiffness and impaired movement, motor treatments, such as Myofascial Structural Integration, may play a beneficial role in the treatment of children with CP. This hypothesis was explored in the three published studies that I participated in with Stanford University School of Medicine.

This paper has three objectives: (1) to describe the rationale for Myofascial Structural Integration for children with cerebral palsy, (2) to present a summary of the results of a previous series of studies1,2,3on young children with spastic cerebral palsy targeting motor function, and (3) to expand on possible benefits of Myofascial Structural Integration based on two in-depth clinical case studies on young children with spastic cerebral palsy.

Myofascial Structural Integration was developed from an earlier Osteopathic theory that structure determines function as much as function determines structure. The implication is that therapy can change function by changing structure. The pioneering insights brought by Dr. Rolf were that myofascia is the organ of structure and movement and that we need to be balanced in the gravitational field. 4,5

“Myofascia is a flexible network of tissue that surrounds, cushions, and supports muscles, bones and organs. It also acts as a riverbed containing the flow of interstitial fluid and is a critical influence on the immune and hormonal systems. In daily life, this connective tissue is an underlying determinant of movement quality, mood, alertness, and general wellbeing.”6While the osteopaths focused on moving bones, Dr. Rolf focused on manually manipulating fascia. A growing body of research confirms the importance of fascia and the myofascial system in many areas.7

Myofascial Structural Integration begins with a semi-structured 10-session series over 3 to 4 months, targeting different areas of the structure at each session. Through manual manipulation and movement education, the trained therapist lengthens and repositions the myofascia towards its typical anatomical position. It is a dynamic educational process. The therapist restrains tissue and asks the client for appropriate movement at the closest joint. When movement is not possible, for example in a child with spasticity, the practitioner can guide the movement until the newfound freedom enables the child to do it for herself.

The theory further asserts that behavior is expressed through the musculoskeletal system. We cannot separate the physical, emotional, mental and spiritual domains of a person.As the motor system evolves, improved behavior patterns in all domains emerge from the individual’s greater sense of competence and the organization of the physical body.4,5

Early in my career, I became interested in working with both able bodied and disabled children. Based on my clinical experience, in 2009, I was invited to join a clinical research team at Stanford University School of Medicine on Myofascial Structural Integration for Young Children with Spastic Cerebral Palsy.The over-arching aim of the studies was to determine if MSI, used as an adjunct to concurrent physical and occupational therapies, could improve gross motor function in young children with spastic CP. In our pilot project1, we enrolled 8 children aged 2 to 7 years with spastic cerebral palsy ofmild to moderate severity.We followed the Gross Motor Function Classification System (GMFCS) levels to characterize the participants: Level I indicates retaining the most functional mobility and Level V the most severely affected. The children in the study were levels II, III, and IV and their functional impairments varied accordingly.We compared results from a 10-session course of MSI to 10 sessions of casual play. The results showed that the treatment led to overall positive change in gross motor abilities, as measured by the Gross Motor Function Measure (GMFM). Six of the 8 children had improvement in their GMFM score. One child with severe cognitive and visual impairment who could not follow instructions did not show change.The other child, 6 years old, Level IV with mixed quadriplegia and cognitive impairment showed improvements in motor function (greater ease in transitioning between positions, began crawling and climbing independently) but the changes did not meet statistical significance.1

The encouraging results led to a second study with a larger team.An initial pilot study using the Gaitrite mat™as a tool to measure aspects of gait for children with cerebral palsy2informed the design of a larger study.In the main study, we enrolled 29 children, less than 4 years of age, GMFCS levelsII, III, and IV.All of the children completed 9 or 10 sessions of the planned 10-session MSI program.3

Notably, 3children who were non-ambulatory began walking during the 10-session series or shortly thereafter. However, we experienced many challenges in using the Gaitrite mat™, including capturing change as a function of the child’s age, ability to cooperate with instructions, and the severity of motor disability. Because of the heterogeneity of the etiology and clinical presentation among children with a diagnosis of cerebral palsy, we concluded it may be more valuable to consider each child individually when determining a treatment’s potential to improve function. While the quantitative data did not show measurable changes in the rate of improvement of gross motor development, secondary analyses suggested qualitative improvements.3

The data suggested that Myofascial Structural Integration might improve aspects of gait and quality of movement including alignment and balance.In addition, many parents reported observed qualitative improvements in their child’s gross motor skills such as improved walking, climbing stairs, sitting cross-legged on the floor and decreased limp.1,3While other qualitative changes were observed by members of the research teams and reported by parents in domains, such as improved sleep, mood, self-care, communication, maturity, and social function, we had not systematically assessed these outcomes.1,3We concluded that further research might consider including additional outcome measures.3This gap inspired the present report.

Over the course of my career I have worked with numerous children with a wide range of disabilities, including many with cerebral palsy. Most of the children with CP that I have worked with have been between GMFCS levelsII and V. I have followed some for a short duration and some I have continued to work with over 12 years. In my work with this population, I have found that Myofascial Structural Integration for children with cerebral palsy must be adapted from the typical 10-session series. The duration ofthe session can be individualized, although most children receive an hour of MSI per session. During the session, children wear soft comfortable clothing. Shoes and sometimes socks are removed. While adult sessions are typically conducted on a bodywork table, sessions for children with CP are usually done on the floor over a rug or carpet with blankets, sheets, and pillows providing extra cushioning and comfort. I allow the child to have toys with them to relax them. Sometimes I do the therapy while the child is watching a movie or listening to music on a device. The children can also sit in the parent’s lap, if they prefer.

At least one parent is always present for the session. Theparent serves as an observer, a support for the child, an encourager, and a chaperone during therapy .Often siblings attend, making this very much a family centered therapy. Sometimes a sibling requests MSI and, with the parents’ permission, they can also receive a session.

Another essential component of the approach is that I always ask the child’s permission to work with them, both at the start of the session and again when starting to work on a new body area or starting a new approach. Even a young baby or non-verbal childcan give their assent or dissent if one knows what to look for.I emphasize that everything is under their control, and I will stop whenever they want. I also typically speak with the child throughout the session, both to reinforce the changes as they occur, (e.g “Can you feel how that moves easier?”), and also with the goal of educating the parents. With these approaches the child and I work in partnership. As their trust of the work and of me grows, they will usually let me work with tender or sensitiveareas, for example hands and arms, that they do not willingly let others touch. The child’s acceptance of Myofascial Structural Integration treatments and joy in receiving it is evident to any observer.

The following are case studies of two children with spastic cerebral palsy using Myofascial Structural Integration that exemplify the changes that are possible, both measurable and immeasurable.

Emery (parents chose name) was born at 28 weeks gestation with Intrauterine Growth Retardation. The pregnancy was complicated by fetal demise of twin B at 20 weeks gestation after a history of twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome, placental insufficiency/abnormal blood vessel insertion, and congenital heart disease. Birth weight was 830 g/1.83 lbs. The child spent 3 months in the neonatal intensive care unit.

I met Emery at age 6 years.She was non-verbal, non-ambulatory, with spastic quadriplegic cerebral palsy, GMFCS Level V.She hadchronic lung disease and fed primarily via gastrostomy tube. She was on a stable dose of Baclofen.

Emery was in kindergarten at a special education school with an individual educational plan in place. She took a bus to school in her wheelchair daily. She had been receiving conventional physical therapy and occupational therapy offered by California Children’s Services since a young age. The parents hoped that the child would make more gains in function than she had to that time with conventional therapy.

I found Emery had bright sparkling eyes, a wide smile that lit up her face, and, as I learned, a very hearty laugh-especially for a small body. Though she was non-verbal, she communicated with facial gestures and the ability to move her head up and down ina large somewhat momentum-driven motion to signify her assent. When I first met her, she had weak head, neck, and trunk control. She was very small, seemed frail, and was very easily startled or distressed.

On our first session, Emery was sitting in her wheelchair and watching me seriously. I smiled, introduced myself, and stayed silent while she made her assessment of me. When she concluded I was okay, I was rewarded with her well-known smile.Both parents stayed by her side in the beginning for emotional support. Over time, they sat by her only when she requested. Weultimately could complete an hour session while one parent was in the room but not actively engaged.

One of the first targets of my Myofascial Structural Integration approach with Emery was working on her ribcage. I reasoned that MSI could facilitate greater ease of respiration which could, in turn, calm her overactivated nervous system.I gently encircled her ribcage in my hands and felt her short shallow respiratory pattern. I guided her towards a slower longer pattern by holding and stretching the fascial tissue and easing restrictions during the breath cycle. Using this approach, she visibly relaxed during the session.

Emery was very averse to touch when we began therapy, especially on her arms and hands.Her hands were so spastic they were in fists and her parents had to place socks on them to protect them. She did not want anyone to touch them. My initial approach was to touch briefly and gently. She gradually became relaxed and comfortable with touch and even welcomed it.She also developed enjoyment reaching out to touch her parents in bed. This enhancement of touch indicated greater feelings of safety, inclusion, and connection as well as pleasure.

I focused in our early sessions on her sacrum, pelvis, legs and back, as well as ribcage. These areas were less sensitive for her than her hands, arms, and neck. I have found that the sacrum is a key area for improvement in motor function as well as decreased sympathetic arousal. Often while supine, the child visibly relaxes while I work on the sacrum from underneath.Each session I would work longer on the hands, arms and neck until she could better tolerate sustained touch. Often working in one area would bring changes in another. Therefore, I would usually work the entire body in a session with a focus on the upper or lower body.

My goal with Myofascial Structural Integration is to free up the very spastic tissue so it is more elastic and in better alignment. Over time, her head and neck control have improved whether she is supine, prone, or seated. While supine, she increased the range of motion in lifting her head and the duration of time she could maintain the lift. This improvement in her head and neck allowed her to be clearer about indicating approval/yes or disapproval/no, a skill that she did not possess and uses beyond oursessions.While prone, if placed in the proper position, she figured out how to use her arms to support herself, keep her upper body and head up and turn to both sides.The increased control of left/right movements while seated resulted in much greater facility with the power wheelchair she used at school. Because of her improvements, she became eligible for a power wheelchair at home through a program of the California Children’s Services.

When she entered treatment, Emery was very uncomfortable when placed on the floor; she often had a noticeable startle response and was clearly unhappy. She spent very little time on the floor and had never laid down on grass. She was almost always in her wheelchair during the day. I made the decision initially to work with her on a bodywork table where she was surrounded and propped up by pillows for both tactile and emotional support. Over time, she accepted being placed on the floor. I gave the parents homework assignments to lay her down in different environments, such as grass and in different positions. Eventually, she could be placed on the floor with no startle response. Her ability to be on the floor led to considerable environmental enrichment for her. She was able to explore independently the many new movements she became able to do from the therapy.

Additional improvements I observed over 13 months of Myofascial Structural Integration:

Additional improvements that parents reported:

“Rolfing has been the best kind of physical therapy our daughter’s received since she was born. We were never happy with the conventional therapy provided through the state’s early start program. [To be honest, we felt it never really helped her where she needed it the most. We gave it time of course, but the sessions didn’t progress in the way that we wanted for her as] …Emery never got the deep tissue stretches or even got out of her wheelchair much in the therapy sessions. We felt helpless.

Emery was introduced to Rolfing at the age of 6, and we didn’t have much expectation because of our previous experience with the state. We just wanted to give our daughter a chance to finally feel better in her own body. Being there since the beginning andactually seeing what is being done to my daughter, we knew this was going to be different.

As the sessions continued, Emery learned more about her body than she ever did with traditional therapy. She would laugh uncontrollably at some sessions, indicating she was getting comfortable in her own body, and having fun.

She would last the whole hour during sessions because she enjoyed it so much and got the opportunity to feel new sensations in her body. She wouldn’t have been able to prior to Rolfing. Her whole body would be very loose after each session, giving her breaks to her constant strong tone, tight muscles, and spasticity. She has more range now, and we are finally seeing positive results for the first time in her journey!”. (Emery’s dad)“She manages her emotions better and is more mature. She seems able to realize her own feelings and control them better. Previously she would go from okay to cry very quickly when something disturbed her. Now she makes a pouty face and doesn’t go all the way to crying. She seems to process it (the emotion) and allows it to pass through her. She is much more relaxed, softer, and more open in daily life and when changing her diaper.” She also shared that previously the singing of Happy Birthday at a birthday party would disturb Emery so greatly that they would have to leave the room. Now she can stay in the room and seems “relatively okay”. (Emery’s mom)

Conclusion of this case: Since Emery has GMFCS Level Vquadriplegia, her physical changes were not related to gait, but to increases in weight/height, mobility, strength and stamina. Her increased physical endurance has given her confidence to explore her physical environment and increases her ability to relate to others. She has more pleasure in movement. She is more willing to try new things. Recently she went ice skating with her adaptive walker and was very enthusiastic and enjoyed being with her school friends in this new activity.

Emery cannot verbalize her impressions of treatment. However, she looked forward to her sessions and was very cooperative. We learned to work through sore, tight areas together and she seemed to feel the immediate relief. Her parents reiterated how much she looks forward to the sessions.

Over the first year of treatment, I saw Emery in my clinical practice about every 2-4 weeks.Based on the improvements we are seeing, we plan to continue Myofascial Structural Integration at this frequency for at least the next year.

Connor (he chose name) was born at 27 weeks gestation, weighing approximately 900g/2 lbs. He was in the neonatal intensive care unit for 75 days. He developed spastic diplegia and was assigned GMFCS Level II. He learned towalk late and wore leg braces which he disliked.His mother reported that he experienced “lots of falling over, which was a source of frustration for him. His muscles hurt a lot while growing.”The family moved to California when he was 2 1/2 years old. He received conventional physicaltherapy and occupational therapy both in his birth location and in California.

I first met Connor when he was 3 years old. He was small for his age, with braces on both legs, and glasses. He was reserved and suspicious of the adults as we assessed him to be a candidate in our first pilot project in 2009.1Later, when I got to know him better, he told me that the doctor (our Principal Investigator) and I were “scary” because we were wearing black. I asked him what color I should wear when meeting new young children. After some thought he said “pink”.

Initially, my biggest hurdle in working with Connor was obtaining his consent. From my clinical experience, I was prepared for this attitude with children (both with and without cerebral palsy) at ages 2-4 as they are learning to exert their autonomy. Connor was feisty and very determined to have his own way. I had to ask permission to avoid his refusals–not “Can I work?” but “Shall we start on your left leg or your right leg?”. If the answer was neither, I offered to be flexible and allow him to choose thearea of his body to start. For my therapy, being touched was a given. Where to start was negotiable.

Since Connor did not have the voluntary control over his physicality, he tried to exert control over his circumstances, including his environment and his relationships. His inability to control led to frustration and more unsatisfactory attempts to controlthe uncontrollable. As his frustration with his circumstances grew, so did his bodily and emotional stress and tension.

Although he was diagnosed with spastic diplegia, the whole body was implicated. Due to the spasticity in the legs, he used other areas of his body, such as his arms and shoulder girdle, to assist with locomotion, balance and proprioception. The increased use of the shoulder girdle and neck increased tension in those areas and adversely affected respiration. Many times, as I worked other areas of his body, his legs would improve. I found that, as with Emery, the sacrum was a key area. As I gently held it andopened the tissue, his whole body would relax. I could feel his respiration deepen and he would stop talking and moving for varying periods of time. Another key area for Connor was the spinal muscles and back. He would request “back work” at each session.

As this component is an important part of the traditional Myofascial Structural Integration series, I was happy to oblige.Although the work was intermittently painful for him, Connor did not tell me to stop. In our interview he said “I remember it being painful, but I felt a lot looser and a lot better, more relaxed afterwards. All of the tension in my legs would loosen and relax.”As we worked together, Connor was able to decrease wearing his leg braces as his legs became more competent and structurally organized. As with most of the children receiving this work, as he grew in height and weight, his health, stamina, and strength improved.

As he experienced more freedom of movement, he exhibited more of the natural curiosity of a young child than he previously had. As he could more easily explore his environment-both physical and relational-his desire for control lessened. As he was able to jump and run, he had an outlet for his intense emotions.

As Connor experienced more joy in movement, and better balance and coordination, the initial negotiations became less prolonged, and he was a much more willing participant. He was very articulate and often provided valuable feedback that allowed me to makemore informed choices about how, what and where to work. My detailed explanations of this to him satisfied his insatiable curiosity. Our partnership to help him realize his goals began to evolve.

When he came for his session, I would sit at the top of a flight of stairs watching him. “Longer legs please” was his constant refrain as he struggled up the stairs to my studio. After one session during our study1when he immediately began to jump, he exclaimed “They ARE longer”.

Connor’s family was pleased with the improvements that Myofascial Structural Integration provided and continued sessions until he was 7 years old and the family moved back to their previous residence. Prior to returning, the family went to Hawaii. Connor was able to run in the sand and surf and play. He managed the entire trip without braces.

Here are some of his accomplishments I observed during the years

Here are the parents’ qualitative observations.

Connor is now 19-a very bright, mature, introspective, and articulate young man. He had many memories of our work together although he was very young.Here are his recollections of the Myoascial Structural Integration treatment.

“As a kid I started to realize I was different. There was a moment when I was 5 years old where the other kids at school made it apparent to me that my physicality wasn’t the same.

I remember that day, coming from school to a Rolfing session, in tears, over the fact I didn’t “fit in” with the other kids.

I had a dream to participate in Taekwondo with the rest of my classmates; however,I thought this wouldn’t be possible for me. When I shared this dream of mine with Karen: her words gave me hope. She said “stick with me and we will get you doing Taekwondo”.

After some time going through the Rolfing sessions, I began to unlock new levels of physicality-I started being able to run and jump which allowed me to fit in more with the others. It was at this moment I was brave enough to give my dream a shot.

Mum signed me up for my first class, and lo and behold, Karen had followed through on her promise-I kicked my first wooden board in half, accompanied by the cheers of my classmates.

A kid who once thought his aspirations were ruled out because of the way he was born, unlocked a whole new world.

I am forever grateful to Karen, for enabling that dream of mine as a child through her work.Now in later life, I am boxing. It’s a huge passion of mine and one which I have worked very hard to develop. It’s thanks to that early life experience: that I learned about the wonders of Rolfing andwas made to feel like I could achieve my goals despite my condition.Thank you, Karen.” (Connor)

Conclusion of this case: In addition to the improvements in gait, balance, and alignment, Connor also gained increased confidence and pleasure in movement. Doing martial arts as a child and boxing now have huge impacts on the quality of his life as well as his physicality. He retained the improvements in his physicality and did not need braces. Both Connor and his mother expressed many times that they often wished “that either you or another MSI practitioner was near us” so Connor could have continued receiving MSI as he grew. I have seen in my private practice the benefits of continuing work through childhood and adolescence. The 10-session series that can often suffice for an able-bodied adult needsto be modified for children with CP. Cerebral Palsy is not a condition that can be “cured”, but it can be managed with continued Myofascial Structural Integration work.

There has been no new published research on Myofascial Structural Integration with children since the three studiesthat we conducted at Stanford University. However, there have been more recent studies on MSI and other manual therapies with adults. A meta analysis including 35 randomized controlled trials with manual therapy as the primary intervention concluded that evidence does support measurable change in posture over time using these therapies.8 A retrospective study on active range of motion using Myofascial Structural Integration with 383 healthy adult subjects over 23 years found significant measured improvement in shoulder flexion, external and internal rotation, and hip flexion.9 Researchers on that study posited that MSI could result in changes in the myofascia that result in a more upright posture leading to a reduction in the inadequate compensatory patterns that we see from fascial thickening and shortening in various conditions.

Although these studies were with adults, it makes sense that the tissue changes resulting from MSI would translate to children. In fact, we saw similar positive structural changes in our studies with children with CP. The difference between those studies and our studies is that with adults one is mainly trying to prevent, or reverse, deterioration whereas with children we are looking for development.

Myofascial Structural Integration is based on the malleability of fascia. For many decades fascia was seen as “packing material” for the organs. Dr Rolf maintained that it is the organ of structure. Research is now showing that due to the contractile behavior of myofibroblasts, fascia may be able to change its stiffness in a short time frame of minutes to hoursand possibly affect motoneuronal coordination.10 Fascia isseen as an organ that connects rather than separates skeletal muscles. Data from studies on fascia and MSI range of motion appear to offer some tantalizing explanations for the structural changes we found in the children with cerebral palsy.

Based on the available research and these two case studies, it appears that MSI has a role to play in the treatment of young children with spastic CP. Current physical and occupational therapy emphasize motor learning, self-initiated and functional activity.11 Myofascial Structural Integration, by contrast, is a structural, hands-on therapy with intensive tactile and proprioceptive feedback. Through lengthening and organizing the myofascial network, MSI increases anatomical alignment which results in better balance in the gravitational field.

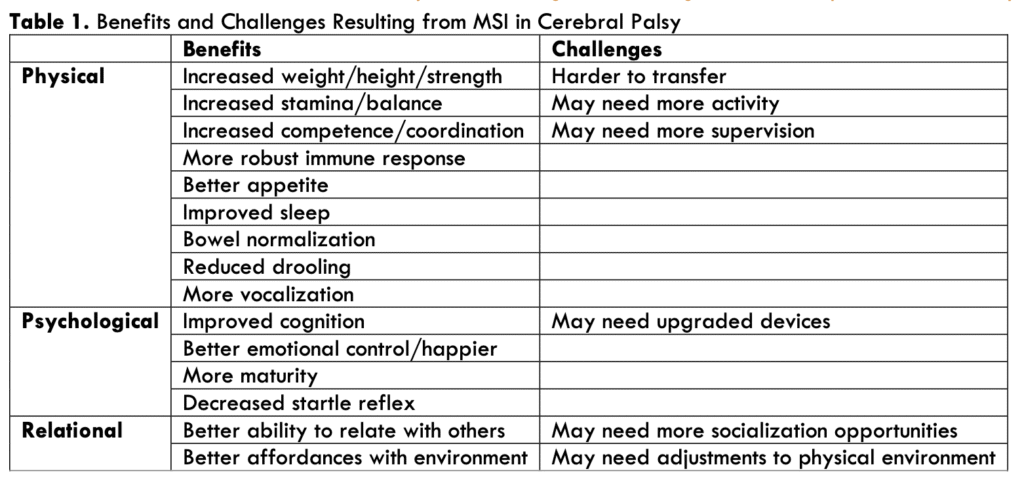

As some of the contractures associated with spastic cerebral palsy are eased, many other physical as well as psychological restrictions are also eased.Although Emery was GMFCS V and Connor was GMFCS II, they nonetheless experienced many of the same benefits physically, emotionally, and in relationships. Some of these benefits are listed in the table below. A key factor with almost all children is the increase in height and weight. Emery went from <1st percentile in both height and weight to the 6th percentile in a year. The physical benefits that cascade from this growth are not only increases in strength, endurance, and stamina, but appear to be increased resistance to infection and normalization of appetite and bowels. Both children improved in coordination, balance, and the joy of exploring movement. Both had increased respiration which offers a host of benefits including relaxation and the ability to moderate emotional responses.

Some of the positive emotional and psychological improvements seen by parents, researchers, and therapists as the child’s structure becomes more organized and less contracted such as being happier and calmer, can be partially explained by research that shows that interventions that reduce contractive postures elicit positive psycho-emotional responses.9,12 Since behavior is expressed through the musculoskeletal system, it makes sense that a therapy such as MSI that positively influences that system towards greater balance and competence shows corresponding effects in the emotional psychological domain.

It is important to understand the interactions among developmental domains within a child11,13. As these children experience increased ease and freedom of movement, they become more able to enjoy exploring their environment with the natural curiosity of childhood. This increased sense of agency gives rise to more mature behavior. All these positively interact to offer a greater quality of life for the children and their families.

In our third study, 3 children who were not ambulatory began walking during the 10-session series or shortly thereafter.3 Although Connor was ambulatory, his balance and gait were adversely affected,and he tripped and fell often prior to receiving MSI. After the sessions he was able to participate in martial arts.

Although gait is a key domain, both of the children whose stories I have highlighted in this paper showed improvement in many domains beyond gait. These changes, though overall broadly beneficial, often bring challenges as well as benefits. In the following table (Table 1) I list the many benefits that appear to result from Myofascial Structural Integration foryoung children with cerebral palsy as well as some potential challenges.

As an example of how this can manifest, the increase in height and weight noted in almost all children usually results in more strength, stamina, and endurance. However, especially for non-ambulatory children, the challenge can be that the increased size makes it harder to transfer them. This example directly pertains to Emery. Having a more competent structure with increased confidence in physicality can lead to the need for more supervision as children naturally begin to move and test their limits. This applies to Connor. I have seen this with the children in our studies, as well as in my private practice. One 2-year-oldchild in one of our studies1was very placid and stayed still on her back on the floor as she couldn’t roll over. After just a couple sessions, she began to roll over and creep (Army crawl). She could now get from one room to another very rapidly and the parents had to “childproof” the home.

From this list, it appears that the many benefits outweigh the challenges. However, knowing in advance the potential for changes that may need to be made in different domains will help with a smoother transition to a higher level of functioning for the child and family.

Both children found increased pleasure in movement and an enhanced ability to explore their environment to whatever degree their diagnoses allowed. Emotionally, both were happier and more relaxed with more confidence. The enhanced functioning brought more ease, comfort, and joy in their relationships with their families and the larger society. Emery began attending more school functions and parties as she could better tolerate the increased stimulation. Connor was able to participate with his friends in activities that he enjoyed. As the children become more self-sufficient there is less stress on the parents. Each positive step improves the likelihood of more positive improvements.

It is important to remember that we are compound multi-dimensional subjects in communication with each other and our environment. Small local physical changes often have large global effects. While, for example, the impacts of small decreases in adductor muscle spasticity and improved voluntary control of tone may not be immediately obvious, the resulting increased facility in diapering can be hugely impactful. As physical ease increases, stress and tension lessen for both caregiver and child. What was a difficult chore, becomes an opportunity for connection. Myofascial Structural Integration can bring about these changes for children and their families. As we continue to work, look for, and evaluate the effectiveness of therapies like MSI to change the outcomes of children with disabilities, what remains with me is the individual wins and feelinga part of each child and family experiencing an ease of a daily challenge, a new connecting activity, or sometimes meeting a major developmental milestone such as walking, and the joy that it can bring.

In our research studies, and in my clinical practice, the youngest children had the best outcomes. Children with cerebral palsy reach 90% of their gross motor potential by age 5, with most potential achieved in the first 2 years.14 Thisindicates the efficacy of beginning to work with children when they are young. As CP begins in infancy, and early diagnosis is becoming available, it is becoming generally accepted that interventions, especially motor interventions should start early.13,14,15Itseems that beginning MSI with infants and very young children during rapid neural development and soft tissue differentiation could have positive effects.I propose that this is an exciting field for further research.

With Myofascial Structural Integration we are taking advantage of the developmental evolutionary urge all organisms possess to grow from infancy to adulthood. By bringing the physical structure toward its anatomical design and in better relationship with the gravitational field, we improve function not only physically, but emotionally, mentally, and in relationship. In my work with children with spastic cerebral palsy both through formal research studies, and with individual clients over the years, I have seen these changes in this population. Therefore, I would conclude that Myofascial Structural Integration may be a reasonable adjunct to other therapies.

I would like to close with a quote from the mother of a 29-month-old child, GMFCS II with spastic hemiplegia who learned to walk and use his affected arm during the 10-session series. “Today, my son walked up to me and gave me a two-armed hug for the first time in his life.”

There are no conflicts of interest.

These children are in my private practice and sessions were paid forby the parents.

I would like to thank the clients and families who graciously allowed themselves to be interviewed and provided medical data, and Heidi M. Feldman MD, PhD and Alexis B. Hansen MD for their generous advice and support in preparing this report.

1. Hansen AB, Price KS, Feldman HM. Myofascial structural integration: a promising complementary therapy for young children with spastic cerebral palsy. J Evid Based Complementary Altern Med. 2012;17(2):131-135. doi:10.1177/2156587211430833

2. Hansen AB, Price KS, Loi EC, et al. Gait changes following myofascial structural integration (Rolfing) observed in 2 children with cerebral palsy. J Evid Based Complementary Altern Med. 2014;19(4):297-300. doi: 10.1177/21565872145404663.Loi EC, Buysse CA, Price KS, et al.

3. Myofascial structural integration therapy on gross motor function and gait of young children with spastic cerebral palsy: a randomized controlled trial. Front Pediatr. 2015;3:74. doi: 10.3389/fped.2015.000744.

4. Rolf IP. Rolfing: The Integration of Human Structures. Dennis-Landman Publishers; 1977.

5. Feitis R, ed. Ida Rolf Talks About Rolfing and Physical Reality. Harper & Row; 1978.

6. Schultz RL, Feitis R. The Endless Web. North Atlantic Books; 1999.

7. Fascia Research Society.www.fasciaresearchsociety.org. Accessed June 24, 2025.

8. Santos TS, Oliveira KKB, Martins LV, Vidal APC. Effects of manual therapy on body posture: systematic review and meta-analysis. Gait Posture. 2022;96:280-294. doi:10.1016/j.gaitpost.2022.06.010

9. Brandl A, Bartsch K, James H, Miller ME, Schleip R. Influence of Rolfing Structural Integration on active range of motion: a retrospective cohort study. J Clin Med. 2022;11(19):5878. doi:10.3390/jcm11195878

10. Schleip R, Gabbiani G, Wilke J, et al. Fascia is able to actively contract and may thereby influence musculoskeletal dynamics: a histochemical and mechanographic investigation. Front Physiol. 2019;10:336. doi:10.3389/fphys.2019.00336

11. Novak I, Morgan C, Fahey M, et al. State of the evidence traffic lights 2019: systematic review of interventions for preventing and treating children with cerebral palsy. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2020;20:1-21. doi: 10.1007/s11910-020-1022-z

12. Elkjær E, Mikkelsen MB, Michalak J, Mennin DS, O’Toole MS. Expansive and contractive postures and movement: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the effect of motor displays on affective and behavioral responses. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2022;17(1):276-304. doi:10.1177/1745691620919358

13. Novak I, McIntyre S, Morgan C, et al. A systematic review of interventions for children with cerebral palsy: state of the evidence. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2013;55(10):885-910. doi: 10.1111/dmcn.12246

14. Morgan C, Darrah J. Effectiveness of motor interventions in infants with cerebral palsy: a systematic review. Dev Med Child Neurol. Published online March 29, 2016. doi.org/10.1111/dmcn.13105

15. Morgan, C., Novak, I., Dale, R.C. et al. GAME (Goals -Activity -Motor Enrichment): protocol of a single blind randomised controlled trial of motor training, parent education and environmental enrichment for infants at high risk of cerebral palsy. BMC Neurol 14, 203 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12883-014-0203-2